by William Gardiner

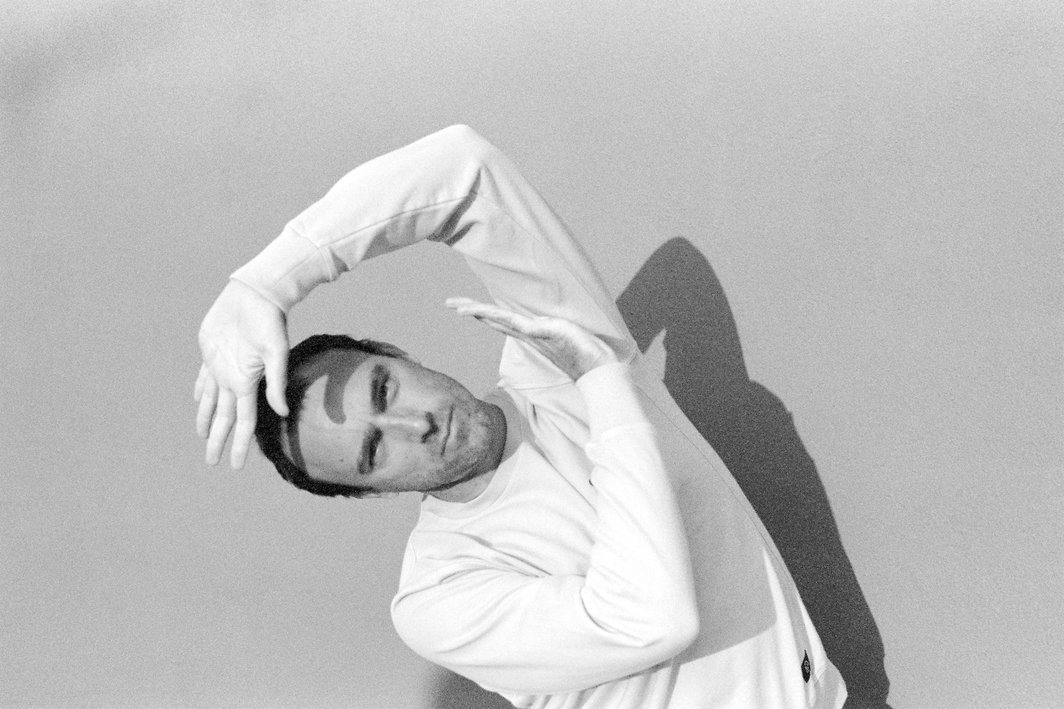

Ben Frost is an Australian composer and electronic musician who has been based in Reykjavík, Iceland for well over a decade now, where together with fellow composers Valgeir Sigurðsson and Nico Muhly, he co-founded the Bedroom Community record label.

Ben is one of my musical heroes, and my interest in his work started long ago and took me all the way to Iceland in the summer of 2016, where I was lucky enough to get to work with him for several months, and we’ve been in touch ever since. So it gives me great pleasure to introduce Ben’s music, and to report on a quick chat I had with Ben about his upcoming piece for Liquid Music as he made his way to the USA from Russia, where he had been performing.

Perhaps a good place to start with Ben’s work is to note that many of the ideas involved in his pieces originate in visual artist sensibilities, and indeed his formal studies were in visual art rather than music. For instance, his most recent record The Centre Cannot Hold was inspired in part by the rich, deep glow of the pigment ultramarine blue, while also being a response to recent political currents. In this sense the work is often highly conceptual, which enhances its ability to reach for and grapple with ideas and issues from the wider world—as will be seen this is very much the case in his upcoming work for Liquid Music.

So that starts to give a sense of the cerebral dimension to Ben’s music. But what really sets Ben’s music apart, for me, is that at the same time as being thoughtful, conceptual, aware, and all of those things, it is at the same time some of the most unabashedly visceral music I know. He has a reputation for making some truly fearsome sounds, which he meticulously places into sometimes unrelenting, even violent arrangements. The boldness, the sheer gall of this visceral quality was what struck me when I first heard his music, and I remember the feeling was disorienting, even upsetting, because something important about how I then understood music was turned on its head: the visceral and the cerebral do not have to be opposites.

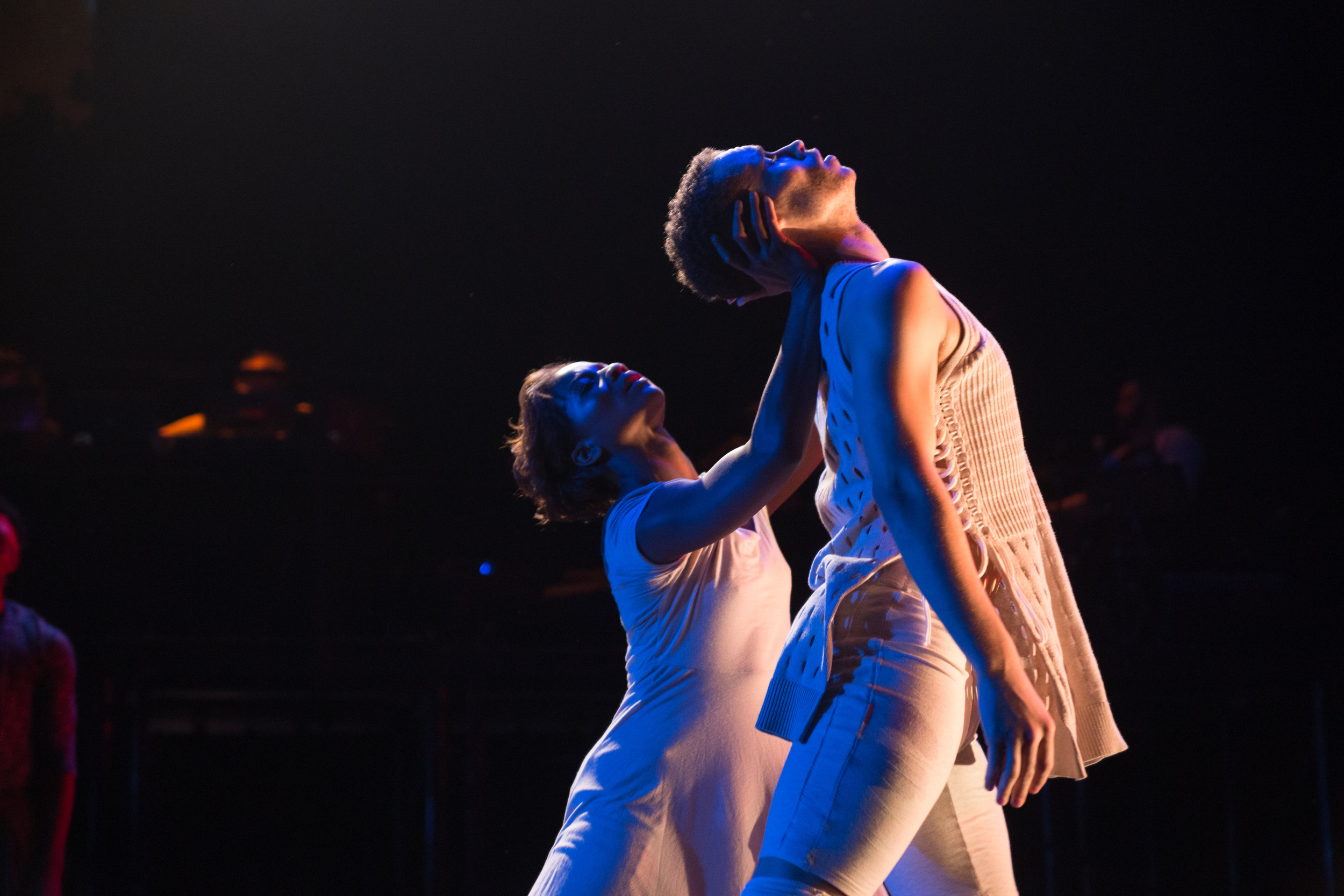

Ben’s piece for Liquid Music, Braids, draws its text from testimonies of three survivors of a human-trafficking disaster that occurred in late 2015 when a boat carrying 300 refugees capsized in the Aegean Sea. Ben Frost was there in artist-journalist mode, together with visual artist Richard Mosse and cinematographer Trevor Tweeten, seeking to document what was going on.

WG: Ben, how did you approach working with the voice in this piece? I know that in the past you have worked very closely with singers—for instance when you directed your opera The Wasp Factory—and the dynamism that results from that is certainly evident in the recording for that piece. Will you be working closely with the singers in this project?

BF: For this piece I used the original interviews I recorded and the individual pacing and phrasing of the speakers to dictate the translation—and it was very much a translation—to notation. When I am dealing with what is ostensibly witness testimony I feel there is a heavy obligation to stick to that testimony as closely as possible.

Creatively I think my work has always benefited from coming up against rules—inherent or self-imposed. I like the way working within strict parameters forces my hand, and makes me work a bit harder, to get away with something. Perhaps it’s a Catholic school thing.

Technically I am taking these recordings, processing the audio to slow down the rate of speech to a more singable pacing, listening to the rhythm of the resulting phrases, and building melodic structures out from those. I don’t write notation in any meaningful way, so by using the audio as a guide it allows me to circumvent the need to work in a traditional way and allows me to instead drag this process back into my realm. In the score there is a great deal left to chance and to interpretation by the ensemble which I’m really excited about seeing play out. These stories are presented democratically; they are ostensibly different camera angles on a singular event. In my mind the way it should work is that the ear functions not unlike a lens pulling focus. All these phrases kind of dovetail in and out of one another in such a way that the language kind of rearranges itself to create a myriad of chance phrases out of individual words unified in space. In my mind this speaks to the secular nature of these events and the unyielding strength of the testimony.

WG: The harrowing texts for your piece, transcribed from interviews with survivors of the disaster, reveal trauma at work, almost in real time. Trauma is a profound concept, and one which I have only recently begun to appreciate more fully in large part due to reading Bessel van der Kolk's book on the subject. It changes people, in ways that can be tragic, but equally: the capacity for resilience people can show, in the ways they adapt in order to survive unthinkable adversity, can be truly inspiring and life-affirming. Could you talk a little about the subject matter this piece deals with?

BF: In the waning tide of human trafficking into Southern Europe, say in comparison to Greece the fall of 2015, I think there is too little attention given to the fact that beyond the trauma of events like the ones described in this piece, even now years later, families, often multiple generations are still divided. Initially by climate change and the ensuing conflicts in Syria and Iraq but now again within the safety of Europe. It is one thing to say, ok, you are welcome to come and live in say, Sweden, as a registered refugee and there is solace in that, but what of the lasting violence of making it a condition of that registered refugee status, that you have no ability to travel outside of Sweden? That you don’t have the rights of other Europeans like myself who can move freely? I have personally witnessed customs officers in Berlin airport now in 2019 straight up racially profiling incoming passengers on flights from other EU countries. Refugees are often never allowed to leave their host country, even though a spouse might be similarly trapped in Greece, parents still in Iraq, even children in another country.

Being a refugee often means being in solitary confinement from everyone you love, sometimes for years. The psychological cost of this is devastating. The same is true in the US for migrants from South and Central America who manage to make it to the U.S.—they can’t leave for fear of risking not being allowed back in, or worse. Epigenetic research is demonstrating that stress-induced rises in cortisol levels such as those inflicted on children at the U.S. southern border when they are ripped away from parents and isolated in a cage—events like that are capable of changing genes. These are state sanctioned intergenerational crimes.

WG: And lastly, could you say a little about what drew you to this project--i.e. contributing a piece as 'rep' as part of a program in which the performers are separate entities to yourself, and present works by several composers? That's a roundabout way of describing the usual situation when presenting 'classical' music, I suppose. Of course you've done it before, notably with Bang on a Can, but it's not so often that we hear your work presented this way; you are more often performing evening length solo sets, your opera projects, scores for dance, and so on.

Frost with LM curator Kate Nordstrum, Berlin July 2015

BF: I suppose simply I don’t really have so much rep to pull from, most of my music doesn’t exist in a traditional score. But also it’s changing shape constantly as I tend to work in a range of scenarios, often simultaneously, which maybe confuses a lot of people? But I’ve been working with Kate for over decade now on a range of projects and so she is one of the few people who kind of gets that irrespective of album cycles, or touring, or film commissions, I am perpetually mulling away on ideas that are often just in need of a gentle push, an outlet. And that is a really precious thing for an artist like myself, to have someone say ‘I have this space, at this time, and these tools- could you imagine that being useful in your current work?’ This is common practice in the visual art world, but not so much in music.

William Gardiner is an Australian composer who works with both acoustic and electronic instruments. He studied composition with David Lang at the Yale School of Music, and has also worked under the mentorship of Ben Frost at Greenhouse Studios in Iceland.

Hear the world premiere of Ben Frost’s new work for ModernMedieval alongside new works from Julianna Barwick and Angélica Negrón and very old works from Hildegard von Bingen

presented by Liquid Music and walker art center

Follow Ben Frost:

WEBSITE || INSTAGRAM || FACEBOOK || TWITTER