By Trever Hagen

Last week an ensemble of 40 musicians performed John Luther Adams’ Crossing Open Ground in Snow Canyon State Park outside of St. George, Utah. Scattered across sandstone and lava flows, the ensemble’s tones emerged and dissipated into desert air revealing a piece that invited audiences not just to listen but to inhabit a soundscape shaped by the land itself. As we left the canyon to trod back to the parking lot, a trail steward said: “Snow Canyon will never be the same.” It made me think about music and change – what must take place in order to significantly alter the perception of place through aesthetics?

How music is involved in change is opaque, undetermined and rarely a matter for contemplation. Yet we have all felt that change in our lives – perhaps an anxious moment is lifted by a song that appears on the radio (your mood: changed); or maybe you’ve just heard a pipe organ at a funeral that has helped you grieve and accept loss (your ontological security: changed); or it’s a song played at basketball game where everyone rises to their feet and begins to clap (your collective body: changed). These are micro-changes of everyday life that music gets into.

There are difficulties measuring change, providing stable units of analysis, or how long change might occur. But something does happen. We could call it magic, yet these moments of change are social experiences underpinned by aesthetics that humans, and groups of humans, have been having since we started playing bone flutes in resonant caves. From music in conflict resolution to music in social movements to turning on the radio in morning. Music, with its property of taking place in real time, brings us from one edge of an experience to another. And that change is, if not measurable, quite observable and felt.

Musical experiences have three distinct points of time: before, during and after. Using these points, we can begin to see and understand how music underpins micro adjustments, changes to the perception of reality, or perhaps attunement to it.

TIME 1: BEFORE

The first unit of temporal analysis of a musical event or experience is the most difficult because “before” refers to everything that has happened to a person that has brought them up to the musical experience. Everything. Childhood, schooling, family, race, class, gender, etc – “before” is the supreme collection of all of your preferences, habits, techniques, tools, skills that have been accumulating in your body and mind that amount to what we call an identity. In an effort to define terms and units to understand change, let’s designate our “Before” as beginning 5 days prior to the performance, when the entire ensemble met in St George, Utah.

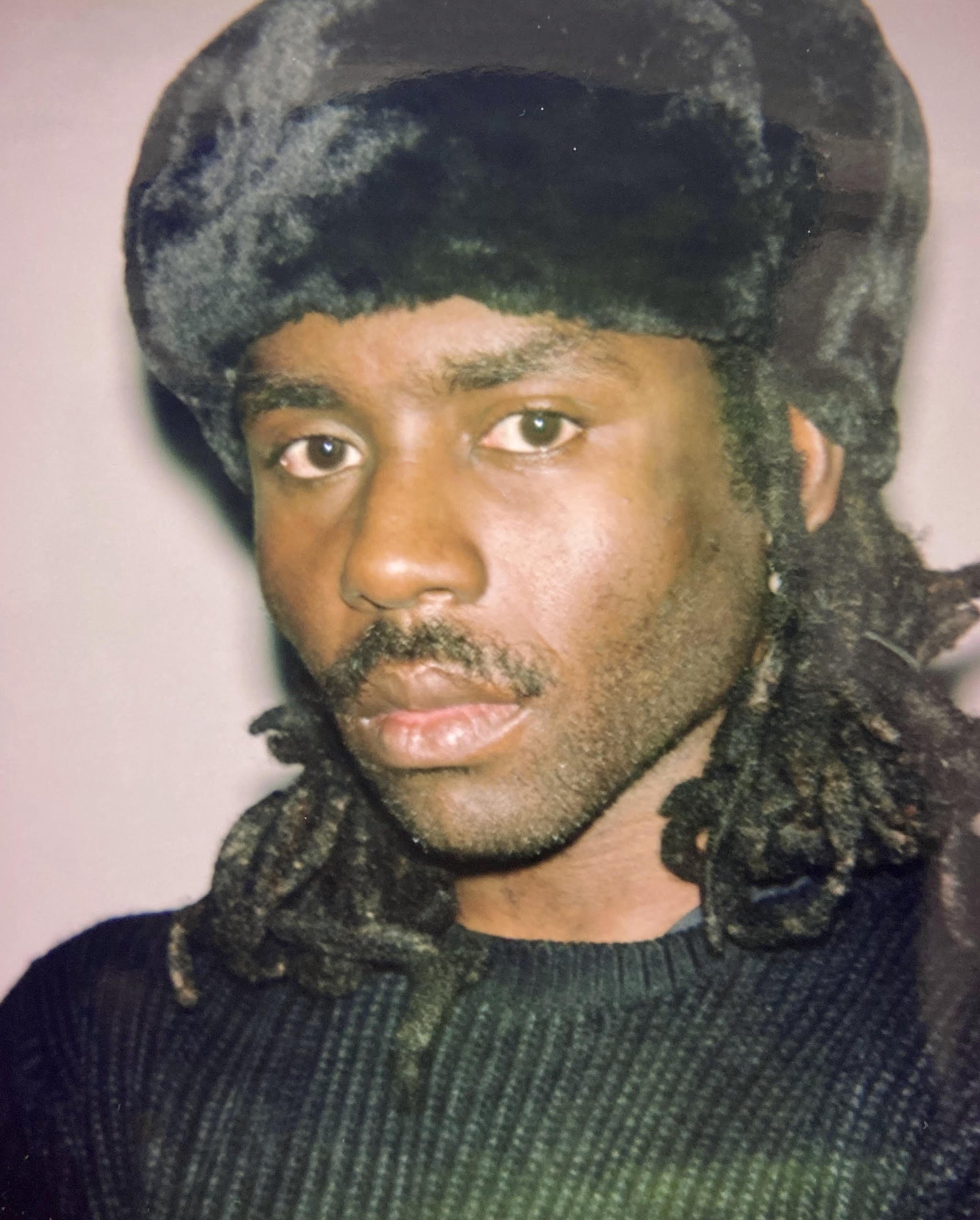

The 40 musicians required to perform Crossing Open Ground were primarily made up of band students from Utah Tech University, along with seasoned section leads from across the US. The important point here is that we had 5 days to rehearse a collective body, not only the music but also getting our bodies onto the same page in order to perform Crossing Open Ground, which requires the ensemble to move across a space. Not something instrumentalists do much of outside of marching band.

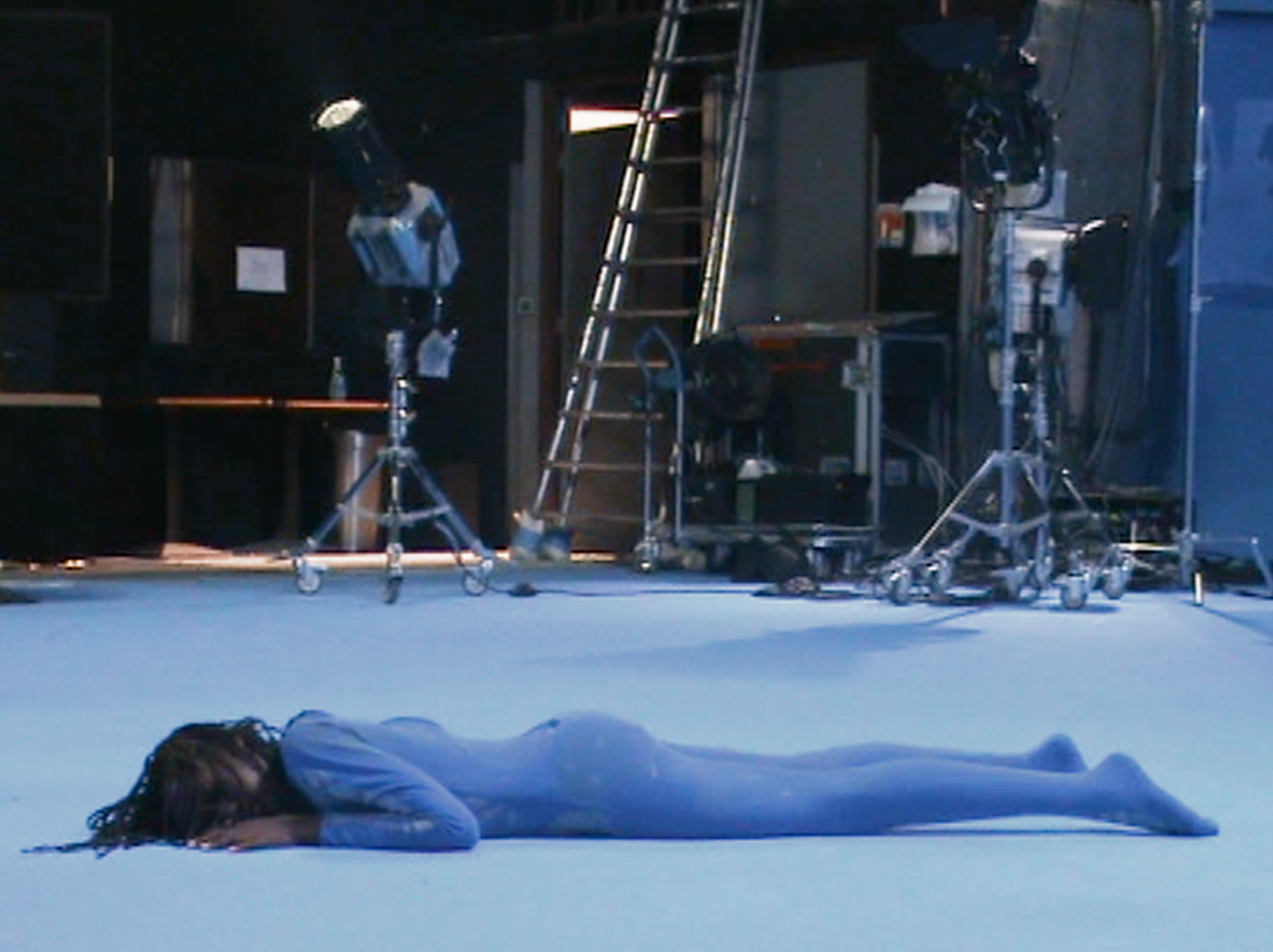

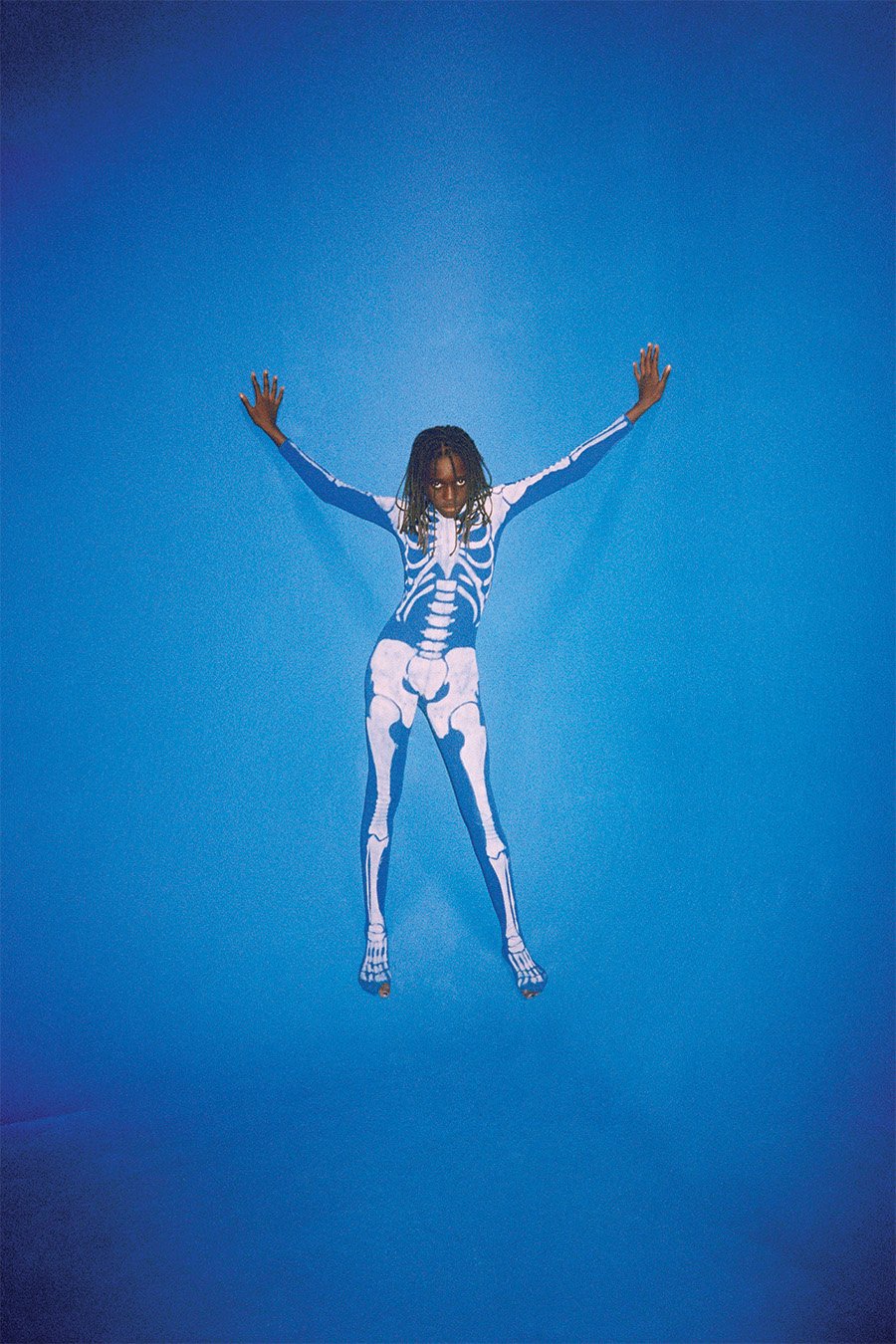

Dimitiri Chamblas, our choreographer, led movement workshops and exercises before we would begin playing everyday. We worked on pacing, corporeal awareness and pair/group action (blindfolded-walking led by a partner, rising up from the ground slowly over the course of 30 seconds, creating human statues, etc). These exercises – new to most of us – had the ensemble working outside our comfort zones, certainly. Yet everyone was up for the task and enthusiastic to incorporate extra-musical direction into the process of learning the piece. Following the collective body work, we staged the movements of Crossing Open Ground off-site giving us our first encounter with intersection of breath, movement, sonic projection and coordination. As this was an entirely novel challenge for many, we were all in the same boat. This was important: our bodies – as an ensemble – were aligning. The beginning of a sense of what could change.

Rehearsing the music proved equally challenging in that Crossing Open Ground doesn’t unfold as other compositions might do. Nadia Sirota was our musical director and guided us through the intricacies of the music and how it unfolds in space and time. The score allows for variable duration—between fifty-four and eighty minutes—because time here is not mechanical but geologic, solar. Time was not a narrative device, as such. Rather, Adams divided the piece into 27 sections, each lasting approximately 2 minutes to give a performance that should be at least 54 minutes. At section 14, we are at the center (or rather climax) of the piece. The musical lines are palindromic units: sections develop from 1 - 13, center at 14, and then the lines 15 - 27 are reversed so you end up playing what you started with. It is up to the discretion of the player to perform the musical line within the unit of time. Often these lines were shared and doubled by other instruments in the ensemble. Thus the performance relies on the decision-making of the individual player within a large ensemble of identical musical material – only a difference in timbre. This was a curious feature that highlights indeterminacy and perception within a closed system.

So drawing together the “Before” experience of rehearsing together, our bodies and collective musical performance were beginning to take shape set against the compositional materials of movement, time and harmony. We were becoming the ensemble and becoming the music.

TIME 2: DURING

Instead of treating composition as an argument with history or technique, Adams approaches sound as an ecology – an interplay between human musicians and the larger systems of earth, air, and time. Thus, the choice of Snow Canyon mattered. The sandstone walls, the desert silence, the shifting thermals – all of these played the piece as surely as the brass and percussion did.

On the day of the performance, listeners walked into the canyon to take their places seated across the natural amphitheater. Once set, the 40 performers entered the canyon and situated themselves across a wide circle at the top of the canyon. The piece begins with gentle percussion and with the woodwinds and brass in the upper register – high up, just as our bodies were perched. As we moved through the 2 minute sections, we descended further into the bowl of the canyon, moving through the audience and down the 30% grade of Snow Canyon. Our musical materials began to drop into the lower registers as we descended. As we moved to the center of Snow Canyon, our circle became smaller, the tones lower and louder with more movement and less breath between phrases. We passed through the center and, beginning our palindromic phrasing, started to walk across to the opposite side of the canyon from where we started. The higher and higher we climbed, the higher and higher our lines became, until we couldn’t go higher and all there was left to hear were the sounds of our breath.

Performing Crossing Open Ground had multiple compositional affordances that differed from a standard score. The music relies less on the conventions of scenes, drama, action and narrative and more on naturally occurring harmonic series – intervals of 2nds, 4ths and 5ths – the type of music that feels like it has always existed and will always exist if we just tune our ear. To this end, the music made possible a different musical experience that wasn’t about one’s personal style or voice but rather like the sublime vision of witnessing something bigger than you that can wash away personal identity; that can reconfigure the dichotomy of human vs nature, or the boundaries of composition vs improvisation.

In short, while playing the piece – the “During” of our three units of time – the music brought me out of modern shackles of the attention technoscape, out of the egotrip of social media, out of the island of self-reliance, out of the economy of consumption. The “During” was collective emplacement in space and time, the “During” was a re-convening with the ways attention is dispersed throughout mind and body, the “During” was dissolution.

TIME 3: AFTER

“Snow Canyon will never be the same,” the trail steward said after witnessing the performance. The site – so mighty in its geologic history – had now been shaped by the impermanent materials of frequencies and breath, engraved in memory. It was clear that the sense of “us-as-ensemble” from rehearsals had grown during the performance to include the audience members, as the trail steward indicates, and the performance site. Human and non-human actors bound together through a shared musical experience.

“Crossing Open Ground is both a journey and a dwelling, a way of moving through a landscape and letting it speak back.”

What is the shelf-life of musical experiences after the final notes pass? Impossible to tell, but no matter how long the afterglow lasts, it hopefully bridges the distance to the next spectacular shared aesthetic experience. Crossing Open Ground is both a journey and a dwelling, a way of moving through a landscape and letting it speak back. Adams’s works expand beyond the concert hall, unfolding in landscapes where silence, wind, and echo become part of the score. This shift sets him apart in contemporary composition: he does not simply write about nature, he writes from it. And that initiative allows us to be a part of nature and art through listening. I can’t think of a more phenomenal effort.

John Luther Adams’s music has always asked us to listen differently. It trains us in the practice of listening. It is environmentalism through perception. In that sense, this performance was not just a concert but an experiment in how art can convene community around land. It is a form of environmental activism – not by protest but by practice. To cross open ground together is to admit we share it, and to listen in that space is to learn how to live within it.

Crossing Open Ground at Snow Canyon State Park was made possible by Kayenta Arts in partnership with Utah Tech University.

Trever Hagen is a trumpet player and scholar, performing and presenting research on sound, music and noise at universities and conferences in the US, Europe and Asia. He is the author of Living in the Merry Ghetto: The music and politics of the Czech Underground on Oxford University Press.

Follow John Luther Adams:

Website: johnlutheradams.net

Follow Trever Hagen:

Instagram: @t.r.e.v.r

Follow Liquid Music for updates and announcements:

Instagram: @liquidmusicseries

Facebook: @liquidmusicseries

Newsletter: liquidmusic.org/newsletter